Rienzi, Wagner’s third opera, was once his greatest success. The performance in Bayreuth is a unique opportunity to rediscover Wagner’s early triumph – where it has never been heard before.

Rienzi

Cast 2026

Conductor: Nathalie Stutzmann

Director: Alexandra Szemerédy, Magdolna Parditka

Stage design: Alexandra Szemerédy, Magdolna Parditka

Costumes: Alexandra Szemerédy, Magdolna Parditka

Dramaturgy: Markus Kiesel

Choral Conducting: Thomas Eitler-de Lint

Cola Rienzi, päpstlicher Notar: Andreas Schager

Irene, seine Schwester: Gabriela Scherer

Steffano Colonna, Haupt der Familie Colonna: Andreas Bauer Kanabas

Adriano, sein Sohn: Jennifer Holloway

Paolo Orsini, Haupt der Familie Orsini: Michael Nagy

Kardinal Raimondo, päpstlicher Legat: Vitalij Kowaljow

Baroncelli: Matthias Stier

Cecco del Vecchio: Michael Kupfer-Radecky

Events

Videobeschreibung zum Trailer Ring der Nibelungen

Monumental, Political, Dramatic.

Rienzi, Wagner’s third opera, was once his greatest success. The story of the Roman tribune combines rise and fall, private tragedy and public vision. The original score is considered lost. This rarely performed work serves as a link between Grand Opéra and music drama, with orchestral power and emotional depth. The performance in Bayreuth is a unique opportunity to rediscover Wagner’s early triumph – where it has never been heard before.

Staging

The 2026 Bayreuth Version

The Bayreuth version for 2026 argues that, had a “final version” been created around 1871, Rienzi would certainly have found its place in the Bayreuth canon of works “from The Flying Dutchman onwards”. For the ten works of the so-called “Bayreuth canon” are not based on a will or authoritative formulations in the foundation deed of the Richard Wagner Foundation Bayreuth, but exclusively on passages from Wagner’s letters to King Ludwig II of Bavaria from 1882.

The team has strived for a version that has considered the aforementioned layers of tradition as carefully as the history of reception. Likewise, the Rienzi philology of recent decades has been meticulously taken into account. Furthermore, the team has attempted to uncover new sources and reconstruct parts of the score believed to be lost.

Form and design naturally lead inevitably to the question of cuts and processes. In this, too, the team followed the musical dramaturgy just as Wagner’s – also later – self-assessments. When Wagner 1871 writes, “they should see the fire in Rienzi; I was a music director and wrote a great opera; that this music director has given them such nuts to crack afterwards, that should surprise them”, one notices the value of this “fire”, which for the later “nuts” was just as indispensable as “every finale like a frenzy, a drunken nonsense of suffering and joy” (1878). But also self-critical things, like the “emptiness that one screws on when one can’t think of anything.” (1879) was taken into account in the version for 2026. Not only a comprehensible sequence of the plot lines was important to the team, but also the internal structure of the individual musical numbers. Here, too, the “unhealthy” relationship between Rienzi and his sister Irene plays an essential role. Not only because it refers to the later incest constellation in the Walküre, but also because it is fundamental to the emotional – and thus musically formed – triangle story Rienzi-Irene-Adriano. For the directorial concept, the question was therefore before their eyes where Wagner musically explored the psychology and emotionality of the characters in their depth. It seemed more important to investigate what politics does to people and not the other way around, and where the music-dramatic treatment of these questions can be found in the score. These emotional constellations – against a background of political history – are what generate the outstanding quality of the individual numbers and scenes in the first place.

Even if Wagner had only written Rienzi, the opera is a unique masterpiece sui generis, which would have found its place in the genre history of European musical theater even without the authorship of the later Bayreuth master.

More information

Genesis

Rienzi – the Last of the Tribunes, Wagner’s third completed opera, is based on the historical novel Rienzi, the Last of the Roman Tribunes by Edward Bulwer-Lytton. In contrast to the novel, Wagner very skillfully enriches the plot with a love story between Rienzi’s sister Irene and the noble Adriano. Wagner was still aware in later years how essential this love story was for an opera against the background of the historical-political plot: “That’s still a tailbone from the French tragedy, where there always had to be an amour; […] my Rienzi lacked this amour for the French; and yet I also had the tailbone there.” Rienzi outwardly stands in the tradition of French Grand Opéra, the most demanding genre of European musical theater – but only outwardly. By choosing a historical subject, Wagner tried to meet the expectations of this genre, as well as in a 5-act structure, and the extensive material offered Wagner many popular scene types, which he used for mass processions and acoustic spatial effects. Rienzi was Wagner’s first great success and marked his breakthrough as an opera composer with its premiere on October 20, 1842, at the Royal Court Theater in Dresden.

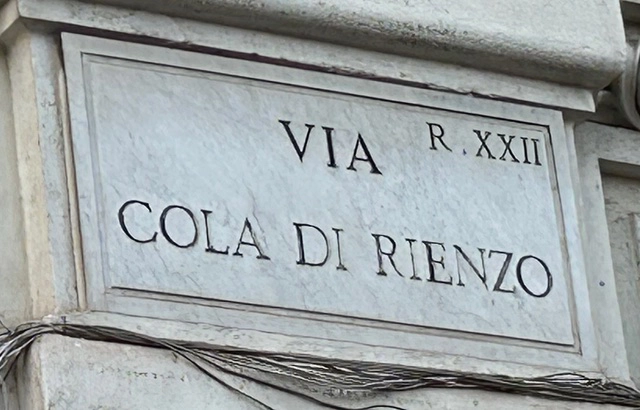

Reception During the Nazi Era

Since the 20th century, the reception of Rienzi has largely been overshadowed by the constantly debated influence on Hitler and its functionalization in National Socialism. Hitler’s self-reflective autobiographical assessment of himself as a tribune of the people who rose from humble beginnings, however, was based on two errors. Firstly, while Cola di Rienzo did come from humble beginnings (though he may also have been a natural son of Emperor Henry VII), he was above all an educated intellectual, a brilliant Latin stylist, and – as a friend of Petrarch – a great literary figure. Secondly, Rienzi’s life decision to become a politician was based on a personal tragedy: the murder of his younger brother by a member of the aristocratic cliques. Both, the intellectual caliber and the biographical trauma, fundamentally distinguish both the historical Cola di Rienzo and the opera character Rienzi from Hitler’s own legend-building.

The Layers of Tradition

Wagner’s original score of Rienzi is lost. There is also no copy or complete performance material from the premiere. A final version of the work only developed in the course of a production process that manifested itself in a first print only after a successful series of performances. Rienzi was also printed only two years after its premiere in only 25 copies (1844). While this edition depicts a stage-ready version, it contradicts the original version in essential parts, so one can assume that Wagner originally planned something else, but could live well with the version that was practicable. In any case, Rienzi was his most successful opera during Wagner’s lifetime and then appeared in numerous adaptations. Wagner earned well from the performances and did not bother with a final new edition. This only changed in 1871 when Wagner again dealt more intensively with the work: For the first edition of his Collected Writings and Poems, Wagner already included a revised libretto of Rienzi in the first (!) volume with numerous cuts, changes, new texts, but also recourse to the first version. Whether this libretto could also have served as a template for a new edition of the ‘final score’ must remain open.

Rienzi and Bayreuth

It was not until after Wagner’s death in 1899 that a new edition of the score and piano reduction, the so-called ‘Cosima’ version, was published. But even when Siegfried Wagner still had a Rienzi for Bayreuth in mind in 1930, he did not see this version uncritically: “Ah yes, the Rienzi! – I’d love to bring that one! […] The main obstacle for us: There are no authentic strokes in the scores! […] But now the question: What should be cut? – My father has indicated quite different strokes for the different stages. […] Which strokes should we make in Bayreuth? Which would be most in the spirit of my father? […] My mother […] undertook a revision of the work in the 1890s. […] With cleverly considered cuts. […] I don’t know if this was the stylistically correct thing to do.” The fundamental problem of an authorized version therefore remained for Wagner’s descendants and thus for the Bayreuth company itself.

In 1957, Wieland Wagner then brought out a radically shortened, dramaturgically highly intelligent, and for its time certainly almost anarchistic-seeming version in Stuttgart, which transformed Rienzi, which was based on Grand Opéra, into a highly exciting music drama.

Nevertheless, despite this confusing material situation, Rienzi is a full-fledged opera that defies both Wagner’s own demands on the concept of “work” and a clear genre-specific classification. Rienzi is neither a Grand Opéra nor a “youthful sin”; it is neither a preliminary stage to later mastery nor the result of time-bound and biographical success strategies!

The Plot

Rome in a time of turmoil: the noble families of the Colonna and the Orsini terrorize the population. The city is virtually without government and sinks into chaos; the Pope, the only moral and spiritual authority, is in exile in Avignon.

Cola di Rienzi, a papal notary and educated man of letters, rises up against the tyrannical noble factions after his younger brother is brutally murdered.

At first, Rienzi wins the support of the Roman people and of the Church and is appointed Tribune. He befriends Adriano, the son of the noble Colonna family, who is in love with Rienzi’s sister Irene, and vows to free Rome from the tyranny of the nobility and to establish an idealistic republic of freedom, unity, and justice, in which only the law prevails and all are equal before it. The Colonnas and Orsinis refuse to accept this; an attempt on Rienzi’s life, however, fails. At the urging of Rienzi’s sister Irene and her beloved Adriano, Rienzi pardons his enemies.

The nobles nevertheless continue to plot his downfall and return with an army. Rienzi leads the Roman citizens to victory—but at a terrible cost. His idealism turns into hubris, and despite his triumph he loses the support of his followers, of the people, and above all of the Church. Adriano also turns away from him. Only Rienzi’s sister remains loyal to her brother and to the ideal of a new Rome. Both are besieged in the Capitol, which is set ablaze by the Roman populace. Even Adriano can no longer save them.