History

On the history of origins of the Bayreuth Festival

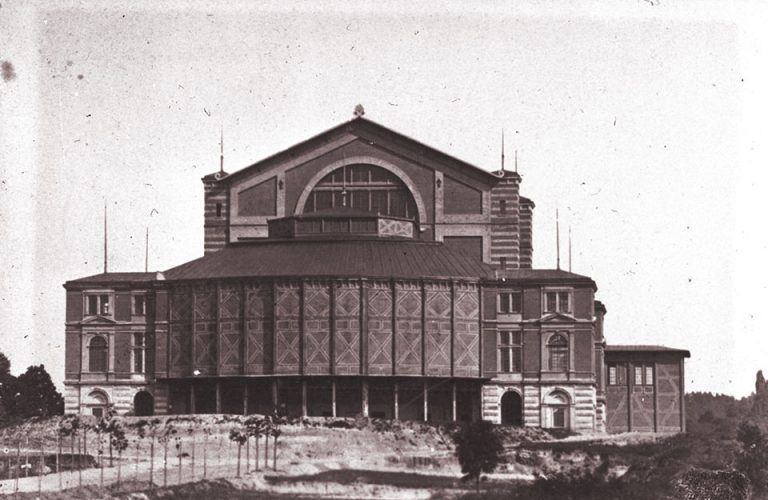

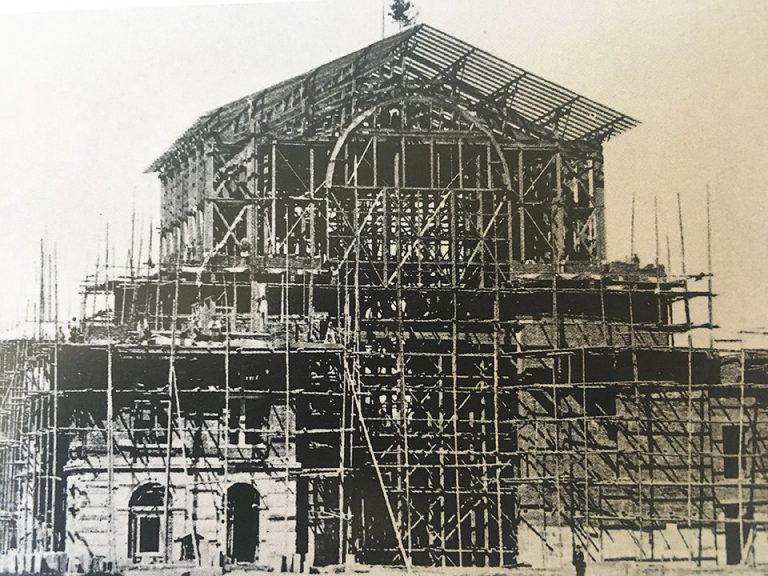

Bayreuth was not the first choice. When Richard Wagner roughly sketched his Festival idea in 1850, his thoughts circled around Zurich or Weimar, and later around Munich. Twenty years passed until, in terms of modern jargon, he “googled” the name of the Frankish gem; Hans Richter had drawn him to the vacant Margravial Opera House of the city of Bayreuth. A year later, the first visit of the town followed, the house proved to be unsuitable for the purpose of the Ring performance, but the city pleased the composer. On 22 May 1872, the foundation was laid, but the construction came to a hold shortly afterwards: the attempt to erect the present-day Festival Hall as a “crowdfunding project” failed because of financial issues. It was only when King Ludwig II provided the necessary funds by means of credit that the construction continued. On 13 August 1876, the first Bayreuth Festival began.

The Festival Idea

“I am genuinely thinking of setting Siegfried to music, only I cannot reconcile myself with the idea of trusting to luck and of having the work performed by the very first best theatre that comes along: on the contrary, I am toying with the boldest of plans […]. According to this plan of mine, I would have a theatre, made of planks, erected here on the spot and have the most suitable singers join me here and arrange everything necessary for this one special occasion, so that I could be certain of an outstanding performance of the opera.”

Richard Wagner to Ernst Benedikt Kietz (1816–1892), 14 September 1850

Richard Wagner, who was born in Leipzig in 1813, collected his first theatre experiences in Magdeburg, Koenigsberg and Riga, where he was the first Kapellmeister from 1837 to 1839. The theatrical building there, called disparagingly “barn” by some musicians, impressed him with its simplicity. The biographer Carl-Friedrich-Glasenapp mentions that Wagner had retrospectively told a musician that three things had remained in his mind: “First of all, the high rising, like an amphitheatre rising parquet, secondly the darkness of the auditorium and third the rather deep lying orchestra. If he ever came to build a theatre according to his wishes, he would consider these three things.”

In 1846, Richard Wagner was appointed Royal Court Kapellmeister of Saxon. Preceding this were the highly successful premières of the Rienzi and Der fliegende Holländer. He came into contact with revolutionary currents in Dresden, dealt with anarchist theses and formulated theses in this social environment to change the theatre and the art business. After he had actively participated in the political rebellions in the city in 1849, he had to run away from Germany overnight. In the Swiss exile, he designed his vision of the “Gesamtkunstwerk of the Future” (a synthesis of many individual forms of art) – and sketched for the first time his Festival idea in a letter to E. B. Kietz. On his desk was also a writing from his Dresden years: a prose preliminary study with the title “The Nibelungensaga” (The Song of the Nibelungs), written in 1848.

The struggle around the Ring

“I intend to perform my myth in three complete dramas that are preceded by a great prelude. With these dramas, though each of them is supposed to form a self-contained whole, I still have no “repertory pieces” according to the modern theatrical elements, but for their portrayal I hold to the following plan: In the course of a specifically designated three-day festival plus a preceding evening, I intend to perform those three dramas together with the prelude. I regard the purpose of this performance as perfectly accomplished if I succeed, along with my artistic comrades, the real performers, in sharing with the spectators who gathered on the four evenings to learn about my intention, this intention to convey artistically real feelings (not critical ones) and understanding. Another consequence is just as indifferent to me as it seems to me superfluous.”

Richard Wagner, A Message to My Friends, 1851

Six years later, Wagner’s “cultural-political background” was followed by the announcement of the Ring: To Theodor Uhlig, Wagner formulated a Festival idea, which can also be read as a kind of twilight of the gods: “I can only think of a performance after the revolution: Only the revolution will bring to me the artists and the audience. The next revolution must necessarily put an end to our whole theatre business: they must and will all break down, this is inevitable… From the ruins, I will then call together to me what I need: I will then find what I need. At the Rhine, I will then set up a theatre, and invite people to a great dramatic festival: after a year of preparation, I shall, in the course of four days, set up my whole work, with which I give the people of the revolution to recognise the importance of this revolution, according to their noblest sense.“

The personal consequences of his participation in the 48/49 revolution in Dresden were only mitigated in 1862, when the King of Saxony issued an amnesty. The composer remained on the run anyway: this time, it was taxpayers and creditors who were harassing Wagner. Although the plans for a future Festival and of the corresponding theatre had taken concrete forms, it was not possible to implement them. The funding should be provided by private patrons – Wagner remained utopian about this. The rescue from the miscalculation took place, in a not particularly revolutionary manner, via King Ludwig II, his future patron. He called Wagner to Munich and wanted to build him a festival theatre there, in which the “Ring des Nibelungen” was to be performed. Gottfried Semper was enlisted as an architect.

Money shortage and laying of the foundation stone

“My friends and valued patrons! Through you, I am placed today in a place which no artist has ever imagined before me. You believe my promise to found for the Germans a theatre of their own, and give me the means to erect this theatre with clear designs before you.”

Richard Wagner at the laying of the foundation stone, 22 May 1872

Semper’s ideas initially saw the idea of incorporating a theatre without boxes in the Munich glass palace, while Ludwig II urged a monumental building on the Isar. The plans did not become more concrete because Richard Wagner wanted to keep control of the project and to build a proper amphitheatre-like building. In 1871, he came to Franconian Bayreuth for the first time, following a recommendation from Hans Richter. Here he visited the Margravial Opera House, recommended for the “Ring” performance, and had to realise that the auditorium was too small for his project. But he took a liking to the city – and it took a liking for him too. To realise his Festival Hall idea, he was given the land in the suburb of St. Georgen. The architectonic planning of the house was taken over by Otto Brückwald, Wagner himself took care of the financing, with varying success. A patronage association, already founded in 1870, was to raise 300,000 thalers to secure the construction of the planned theatre and the costs of the performances. The foundation was laid on 22 May 1872. On this occasion, Richard Wagner conducted Beethoven’s ninth Symphony in the Margravial Opera House. Fifteen months later, at the topping-out ceremony in August 1873, a large fireworks display over the city announced the future Festival Hall.

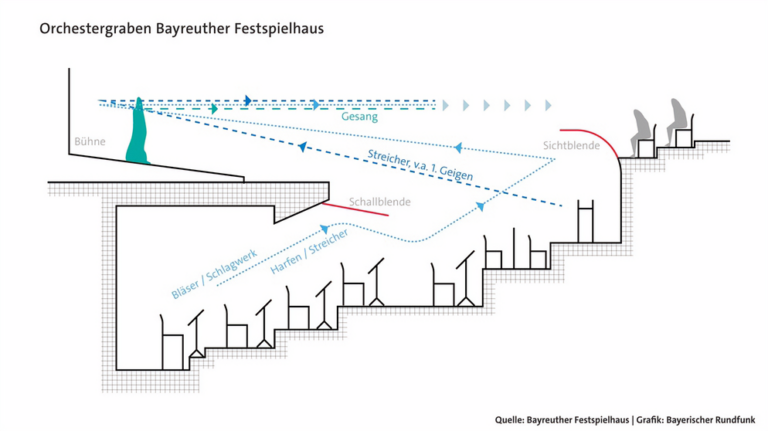

The orchestra pit

The acoustics of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus are unique. Fans and musicians around the world rave about the legendary mixed sound on the Green Hill. The fact is that the sound miracle is not the work of an ingenious acoustician, but a coincidence. But one with symbolic value: the special acoustics are a by-product of Wagner’s aesthetic vision of the perfect illusion and a democratic theater. “Oh my invisible, lower, transfigured orchestra in the theater of the future” – Richard Wagner dreamed so rapturously as early as 1865 in Munich at the premiere of his ‘Tristan’. If only the pit were invisible, so that there was nothing between the audience and the stage to distract from what was happening on stage. That was the composer’s thinking. Wagner’s theatrical vision was not primarily shaped by acoustic considerations, but by visual and idealistic ones. As an antithesis to the magnificent, representative theater buildings of his time, the political revolutionary placed the functionality of the house in the foreground.

His goal: the perfect illusion for everyone. The traditional side boxes had to be omitted because there was to be no hierarchy in the audience, and also because the orchestra and the other audience members could have been seen from there. However, the guests should go to the theater for the sake of the work, not to see or be seen. At the same time, the fan shape of the auditorium, quoting the ancient amphitheaters, was intended to give his festivals a democratic, civic feel in the style of ancient Greece.

In the spirit of perfect illusion, Wagner also dispensed with too many ornaments in the hall, was the first to ensure darkness during the performance and had the “technical hearth of the music”, as he called the orchestra, placed in steps downwards and disappear under the stage. Wagner found inspiration for this during his time in Riga in the theater there. During the construction work in Bayreuth, the pit was extended twice to provide sufficient space for the large orchestra: once under the stage and once at the front, so that the first rows of seats disappeared.

The instruments in the mystical abyss are arranged according to volume, the loudest at the bottom and the quietest at the top. At the first festival in 1876, Wagner noticed that although the string sound blended well due to the reflection of the screen, overall it was still drowned out too much by the wind instruments. So in 1882, during rehearsals for “Parsifal” – keyword: workshop – a sound screen was installed under the edge of the stage to muffle the wind instruments. As a result, the sound of the winds and percussion, which was muffled by the sound screen – also known as the “Parsifal screen” – hit the sound of most of the strings in the screen and was reflected from there onto the stage. This is precisely the big difference to most other theaters. What the Bayreuth audience hears is not direct sound from the pit, but almost exclusively reflected sound.

13.8.1876: “Vollendet das ewige Werk”

“’I did not believe you would do it’, said the Emperor. But who did not share this disbelief? …If I ask myself seriously who has made this possible for me, that on the hill near Bayreuth there is erected a completely executed large theatre-building, according to my specifications, which must be imitated by the whole modern theatre-world, with the best musically-dramatic forces gathering around me in order to voluntarily undertake an unprecedented new, difficult, and exhausting artistic task, and to accomplish it with pleasure to their own astonishment, I can first of all only point to these effective artists … “

Richard Wagner in retrospective on the first Festival

Success looks different: the first Festivals (with three cycles) ended in a financial disaster (approx. 1.1 million euros deficit); the Festival Hall was empty for six years after that. However, Richard Wagner did not resign artistically, and he also negotiated a financing contract with Munich: Bayreuth received an interest-free loan of approx. 750,000 euros based on today’s prices, which was repaid from royalties of the Munich Wagner performances. For Bayreuth, he announced the performance of all the main works – which was later enforced by Cosima Wagner after 1886. “Parsifal” was premiered on 26 July 1882. Six months later, Richard Wagner died in Venice. His grave lies in the garden of the house “Wahnfried”.