Bayreuth was not the first choice. When Richard Wagner roughly sketched his festival idea in 1850, his thoughts revolved around Zurich or Weimar, later also around Munich.

History

On the genesis of the Bayreuth Festival

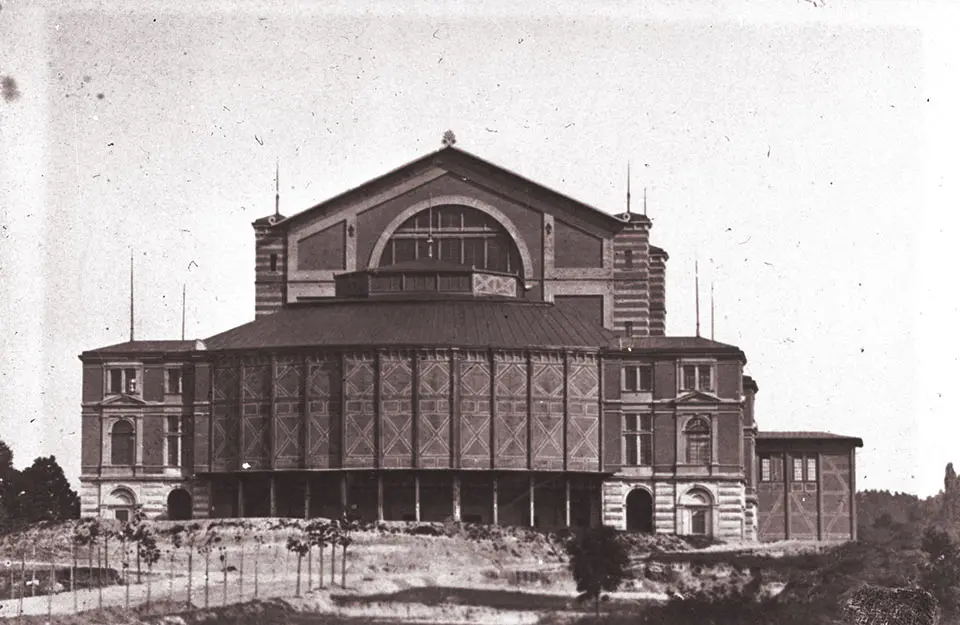

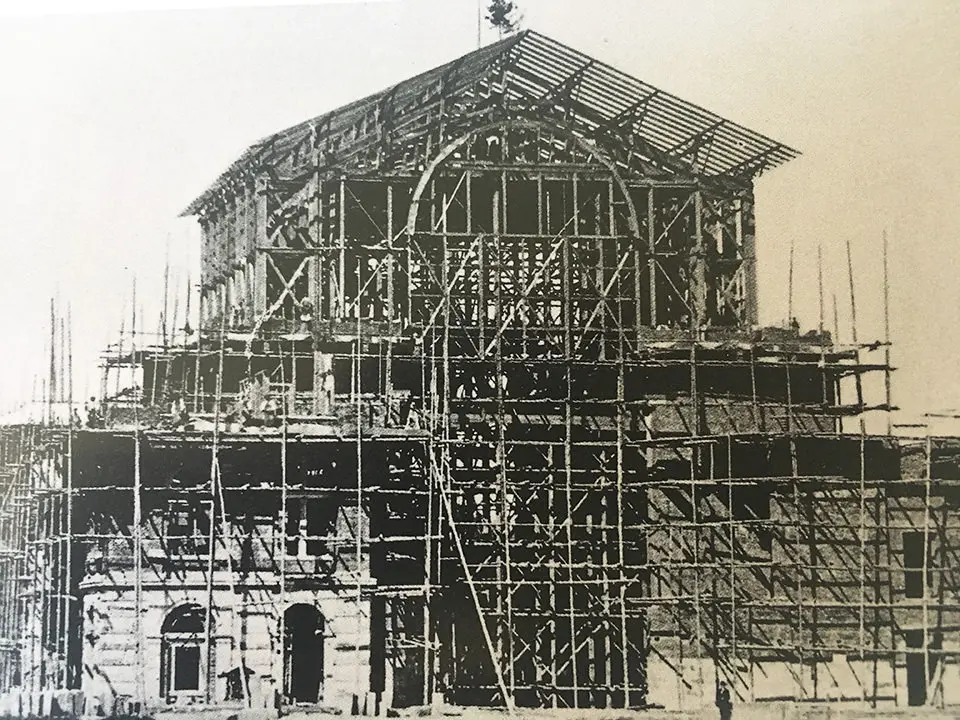

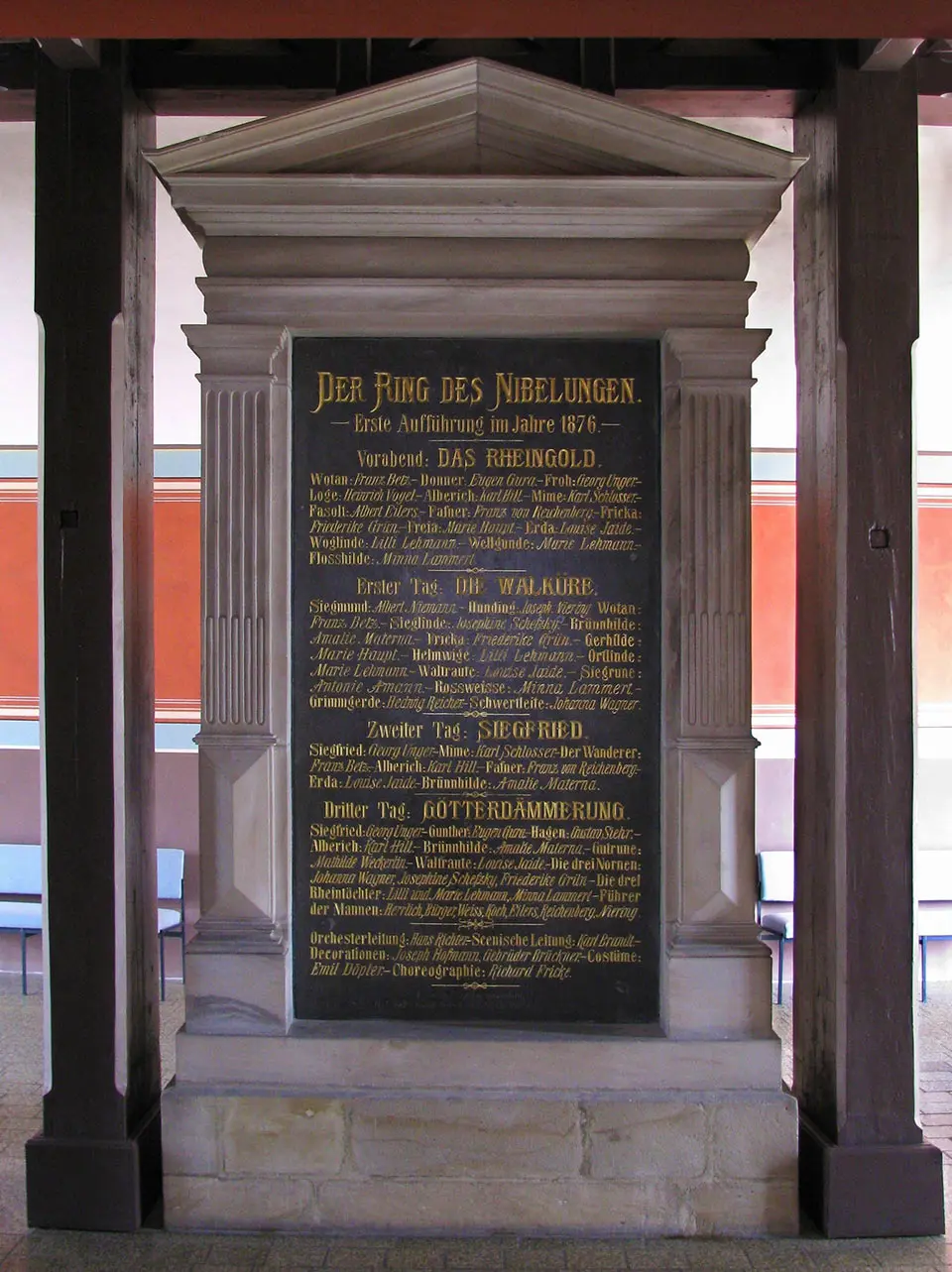

Twenty years passed until he “googled” the name of the Franconian jewel in the conversation lexicon, Hans Richter had drawn his attention to the vacant Margravial Opera House in the city of Bayreuth. A year later followed the first visit to the city. The house proved unsuitable for the purpose of the Ring performance, but Bayreuth pleased the composer. The foundation stone was laid on May 22, 1872, but the construction soon came to a standstill: The attempt to build today’s festival hall as a “crowdfunding project” failed. Because of the money. Only when King Ludwig II provided the necessary funds by credit, the construction finally picked up speed, so that on August 13, 1876 the first Bayreuth Festival could begin.

The Festival Idea

“I am thinking of really setting the Siegfried to music, but I am not inclined to have it performed at random by the first best theater: on the contrary, I am entertaining the boldest plans […] Then I would have a theater built here […] according to my plan out of boards, have the most suitable singers come to me and have everything necessary for this one special case made for me in such a way that I could be sure of an excellent performance of the opera.”

Richard Wagner to Ernst Benedikt Kietz (1816 – 1892), September 14, 1850

Richard Wagner, born in Leipzig in 1813, gained his first theater experiences in Magdeburg, Königsberg and Riga, where he was employed as first Kapellmeister from 1837 to 1839. The local theater building, disparagingly called “barn” by some musicians, impressed him with its simplicity. The biographer Carl-Friedrich-Glasenapp mentions that Wagner told a musician in retrospect that three things had remained in his memory: “Firstly, the strongly ascending parterre, rising in the manner of an amphitheater, secondly the darkness of the auditorium and thirdly the rather deep-lying orchestra. If he ever came to build a theater according to his wishes, he would take these three things into consideration.”

In 1846 Richard Wagner was appointed royal Saxon court conductor. This was preceded by the extremely successful premiere of Rienzi and that of The Flying Dutchman. In Dresden he came into contact with revolutionary currents, dealt with anarchist theses and, in this social environment, formulated theses on changing the theater and art business. After he had actively participated in the uprisings in the city in 1849, the now wanted man had to flee Germany overnight. In Swiss exile, he designed his vision of the “Gesamtkunstwerk of the future” – and sketched his festival idea for the first time to E. B. Kietz. On the desk was also a writing from his Dresden years: a prose study from 1848 entitled “The Nibelungensaga”.

The Struggle for the Ring

“I intend to present my myth in three complete dramas, which are to be preceded by a great prelude. With these dramas, although each of them should indeed form a self-contained whole, I nevertheless do not mean any ‘repertoire pieces’ according to modern theater concepts, but for their presentation I adhere to the following plan: — At a festival specially designated for this purpose, I intend to perform those three dramas together with the prelude in the course of three days with a preliminary evening: I consider the purpose of this performance to be fully achieved if it succeeds me and my artistic comrades, the real performers, to artistically communicate this intention to the spectators who gathered to get to know my intention, to a real feeling (not critical) understanding on these four evenings. A further consequence is as indifferent to me as it must appear superfluous to me.”

Richard Wagner, A message to my friends, 1851

The announcement of the Ring was followed half a year later by the “cultural-political background”: Wagner formulated a festival idea to Theodor Uhlig, which can also be read as a kind of Götterdämmerung: “I can only think of a performance after the revolution: Only the revolution will bring me the artists and the audience. The next revolution must necessarily bring an end to our entire theater industry: they must and will all collapse, this is inevitable… From the rubble I then gather together what I need: I, what I need, will then find. On the Rhine I will then set up a theater, and invite to a great dramatic festival: after a year of preparation I will then perform my entire work in the course of four days: with it I will then make the people of the revolution recognize the meaning of this revolution, according to its noblest sense.”

The personal consequences of his participation in the 48/49 revolution in Dresden were only mitigated in 1862, when the King of Saxony issued an amnesty. The composer remained on the run nonetheless: this time it was tax investigators and creditors who were bothering Wagner. Although the plans for a future festival and the associated theater had taken concrete form, an implementation was not to be thought of. The financing was to be provided by private patrons – here Wagner remained a utopian. The rescue from the miscalculation came, not very revolutionary, through King Ludwig II, his future patron. He appointed Wagner to Munich and wanted to build a festival theater there in which the Ring des Nibelungen was to be performed. Gottfried Semper was recruited as an architect.

Money Woes and Laying the Foundation Stone

“My friends and valued patrons! Through you I am today placed in a position such as no artist has ever occupied before me. You believe my promise to found a theater of their own for the Germans, and give me the means to erect this theater in a clear design before them.”

Richard Wagner at the laying of the foundation stone, May 22, 1872

Semper’s ideas initially provided for the installation of a box-free theater in the Munich Glaspalast, while Ludwig II pushed for a monumental building on the Isar. The plans did not become more concrete, also because Richard Wagner wanted to retain control over the project and erect a functional amphitheater-like building. In 1871 he came to Bayreuth in Franconia for the first time, after a recommendation by Hans Richter. Here he visited the Margravial Opera House of the city, which was recommended to him for the Ring performance, and had to realize that the auditorium was too small for his project. But he liked the city – and it liked him. To realize his festival theater idea, he was given the property in the suburb of St. Georgen as a gift. Otto Brückwald took over the architectural planning of the house, Wagner himself took care of the financing – with fluctuating success. A patronage association founded as early as 1870 was to raise 300,000 talers to secure the construction of the theater, which was planned as a provisional, and the costs of the performances. The foundation stone was laid on May 22, 1872, on which occasion Richard Wagner conducted Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in the Margravial Opera House. Fifteen months later, for the topping-out ceremony in August 1873, a large fireworks display over the city announced the future festival theater.

It took four years for the building to be completed. What sounds breathtakingly fast for today’s time almost turned into a disaster for Wagner’s construction plans. Several times the construction threatened to fail, craftsmen could no longer be paid, the interest of potential festival guests remained behind expectations. Ludwig II left requests for money from his revered composer unanswered for a long time, until he granted a loan in 1874 (according to today’s standards about 1.7 million euros; this was fully repaid by the Wagner family by 1906). In November 1874, with the Götterdämmerung, the composition of the Ring des Nibelungen was completed, and in the following summer the rehearsals for the first cyclical complete performance began.

The Orchestra Pit

The acoustics of the Bayreuth Festival Theater are unique. Fans and musicians around the world rave about the legendary mixed sound on the Green Hill. The fact is: Behind the sound miracle is not a brilliant acoustician, but chance. However, one with symbolic value: The special acoustics are namely a by-product of Wagner’s aesthetic vision of the perfect illusion and a democratic theater. “Oh my invisible, deeper, transfigured orchestra in the theater of the future” – Richard Wagner raved so enthusiastically as early as 1865 in Munich at the premiere of his “Tristan”. If only the pit were invisible, so that there would be nothing between the audience and the stage that distracts from the stage action. That’s what the composer thought. Wagner’s theater vision was not primarily characterized by acoustic, but by visual and ideal considerations. As a counterpoint to the magnificent, representative theater buildings of his time, the political revolutionary placed the functionality of the house in the foreground.

His goal: the perfect illusion for everyone. The traditional side boxes had to be eliminated because there should be no hierarchy in the audience and also because you could have seen the orchestra and the other spectators from there. But the guests should go to the theater because of the work, not to see or be seen. At the same time, the fan shape of the auditorium, quoting the ancient amphitheater, should give his festivals a democratic-bourgeois character in the style of Greek antiquity.

In the sense of the perfect illusion, Wagner also dispensed with too many decorations in the hall, was the first to ensure darkness during the performance and had the “technical hearth of music”, as he called the orchestra, set down in steps and disappear under the stage. Wagner found inspiration for this during his time in Riga at the local theater. In the course of the construction work in Bayreuth, the pit was widened twice to provide sufficient space for the large orchestra: once under the stage, once to the front, so that the first rows of seats disappeared.

In itself, the instruments in the mystical abyss are sorted according to volume, the loudest at the bottom, the quietest at the top. At the first festival in 1876, Wagner noted that the string sound mixed well due to the reflection of the screen, but was still drowned out too much by the brass section overall. So in 1882, during rehearsals for “Parsifal” – keyword: workshop – a sound baffle was installed under the edge of the stage to dampen the brass section. The result: The sound of brass and percussion dampened by the sound baffle – also called the “Parsifal baffle” – hits the screen on most of the strings and is reflected from there onto the stage. This is precisely the big difference to most other houses. What the Bayreuth audience hears is not a direct sound from the pit, but almost only reflection sound.

August 13, 1876: Completes the Eternal Work

“I didn’t believe you would bring it about,” – the Emperor said to me. But by whom was this disbelief not shared? …If I seriously ask myself who made it possible for me to have a completely executed large theater building, entirely according to my specifications, erected by me there on the hill near Bayreuth, which the entire modern theater world must remain impossible to imitate, as well as that in this theater the best musical-dramatic forces united around me to voluntarily undergo an unprecedented new, difficult and strenuous artistic task, and to solve it happily to their own amazement, then I can primarily present only these realizing artists themselves…”

Richard Wagner in retrospect on the first festival

Success looks different: The first festivals (with three Ring cycles) ended in a financial disaster with a deficit of about 1.1 million euros. The festival hall then stood empty for six years. But artistically, Richard Wagner did not give up, and he also negotiated a financing agreement with Munich: The Bayreuth Festival received an interest-bearing loan of about 750,000 euros, which was repaid from royalties from the Munich Wagner performances. Wagner announced the performance of all major works for Bayreuth – enforced after his death by Cosima Wagner from 1886. Wagner’s last work Parsifal premiered on July 26, 1882 at the second Bayreuth Festival. Half a year later, Richard Wagner died in Venice. His grave is located in the garden of the house “Wahnfried” in Bayreuth.